The Vocal Mirror: a tool for change

Outlining a technique that helps explore the unconscious purposes of vocal behaviours. Therapists can train to use this technique, and voice practitioners can extend their intervention skills with clients who seem ‘stuck’ and apparently resistant to the more ‘mechanical’ remedial work undertaken in the voice professions.

[A version of this article was originally presented at the May 2002 AGM of the British Voice Association as Finalist for the prestigious Van Lawrence Prize, and then published in Oxford Psychotherapy Society Bulletin 36, Nov. 2002, pp. 15-17]

Voice as mirror (or echo) of the self

As a voiceworker, I understand a person’s voice as expressive of the whole self. How a person’s voice sounds depends on how they use their breath and different muscle groups. And how a person ‘lives’ in their body reflects their inner states (emotional and psychological). As our thoughts and feelings fluctuate, our body responds; habitual patterns of feeling, thinking or behaviour begin to show as physical characteristics, certain ways of standing, moving and sounding, thumb-prints’ by which we know ourselves and are recognised by others.

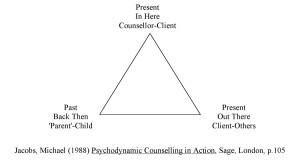

The ‘Vocal Mirror’ (as I have called it) is a technique I have developed and been teaching to therapists and counsellors over the last 4 years. Using a client’s vocal and non-verbal behaviour, the therapist can help her discover more about what underlies her ways of relating to others, and how the world appears to respond to her. Drawing upon the triangle of insight (see figure), this tool helps raise the client’s self-awareness, and engages her own sense of responsibility.

The principle is that how the client behaves with the therapist may well be similar to how she behaves with others in her life, to the extent that it is, at least partially, representative of the client’s patterns of relating and communicating elsewhere. And such patterns of relationship and communication inside and outside the consulting room may well have begun many years previously, as far back as childhood.

The principle is that how the client behaves with the therapist may well be similar to how she behaves with others in her life, to the extent that it is, at least partially, representative of the client’s patterns of relating and communicating elsewhere. And such patterns of relationship and communication inside and outside the consulting room may well have begun many years previously, as far back as childhood.

The Vocal Mirror in action

In Mary’s opening consultation with me, she said that she would like to explore her voice because she had some problems with it. As she talked, I realised that I was finding very difficult to identify what she thought those problems were. I noticed two things; first, her voice was very quiet, with only the tiniest thread of breath support; second, I felt extremely drowsy (an experience I was to have in her sessions on several subsequent occasions).

Step 1 – copying the client’s vocal style

25 minutes into the consultation, as, even after direct questioning, I still had gained no clear idea what Mary perceived to be her voice problem(s), I asked her permission for us to conduct a short experiment, and to use what I called the ‘vocal mirror’. Once she agreed, I began to talk to her, copying as best I could her vocal style. I explained that I was not a very good mimic or impersonator, so I would only be able to give her a very rough imitation of how I heard/experienced her voice and her body positions and movements, and I made it clear that I would not try to copy her language or phraseology. It is important that this exercise is done with deep respect for the client, and it should not feel like mockery, or the client’s defences – quite reasonably – may be triggered. As I continued to speak, I was careful to minimise any interpretation of her vocal style, and confined myself to describing its physical characteristics.

“As I speak to you, I’d like you to notice the volume of this person’s voice, its speed. Notice the gaps between statements, and how this person licks her lips and swallows before she says the next sentence. As I speak in this style, I notice how sparse and shallow my breathing is. As you sit opposite this character speaking like this, note your reactions – what happens? What are you feeling, what are you thinking?”

Step 2 – the client notes her reactions

I continued to speak in this way for about 20 minutes as we conversed, asking Mary to notice her changing reactions, what she felt, what she thought, what she did. At first, she was shocked; she then said that she felt like her energy was being sucked away by this person; as I persisted in this style, she said that she began to feel sleepy and confused; as I still persisted in the style, she began to feel frustrated, wanting it to stop, and then wanting to ‘get away’.

Step 3 – the client considers patterns of reaction in others

I asked Mary whether she recognised any of those reactions as being something that happened in others when she spoke with them, and she replied, ‘Yes.’ This was a new level of awareness for Mary. She realised that something in her own communicative style may have been evoking a particular pattern, range or sequence of responses in others.

Step 4 – the client considers outcomes as clues to unconscious purposes

Had we stopped at this point, Mary have simply felt a victim of others’ ‘unfair’ and ‘ignorant’ reactions to her. Perhaps she would have claimed that the impression she was giving off was not her intention at all and that she was simply ‘misunderstood’.

The next step, therefore, was to suggest a ‘thought experiment’. I put it thus: “Assume for a moment that this person over here, this character (i.e. me) intended to evoke the kinds of reaction that you were having. Why might they want to do that? What does it seem to achieve?” This can meet with initial confusion. Mary saw the effect of the communicative style as so negative, she could not immediately see any good reason for someone communicating in that way. I asked therefore what seemed to be the outcome of this communicative style of ‘mine’ on her. She said that it seemed to keep her quite distant and ‘safe’ from me, and make her lose interest in me.

I asked her whether she thought that maybe, at some level, some part of her may even want to evoke such a pattern of response in others. It is important to find ways to help a client explore the possible unconscious (or not so unconscious) purposes of vocal behaviour. It can also help the therapist gauge the client’s level of awareness, and preparedness to acknowledge, explore and take responsibility for their unconscious processes generally.

Mary acknowledged that secretly she often wanted people to respond in these ‘negative’ ways. This was a second important insight for Mary; she realised that her vocal and communicative ‘dysfunction’ might have a purpose; it kept her safe, and insulated her from people getting too ‘close’, or her getting too close to her own feelings. Alongside this came the realisation that part of her that wanted to sustain this pattern of relating, and that this threatened to undermine any change work she might want to do.

Step 5 – responding to the material that has emerged

Interestingly, in reaction to Mary’s vocal style, I had felt the same drowsiness and ‘fogginess’, then the frustration, and the desire to escape that Mary reported around my copy of her style, But Mary offered so much more with the comment about being shocked, and her energy being sucked away. Her reactions seemed to mirror a kind of emotional biography. In the 3 years we have worked together, we have been able to expand on many of those first reactions she had in the initial consultation: the ‘shock’ had a parallel in the shocks she receive d as a child at her parents’ hands; the experience of feeling drained has taught her about her relationship to her mother who demanded so much ‘mothering’ from her, and her trying to protect her father from his own fears; her ‘drowsiness’ opened into several months of exploring the story of ‘Sleeping Beauty’, and her own journey from escaping into her own daydreams through to wakefulness and the greater awareness of adulthood; the frustration her vocal style evoked in others, along with the desire to get away led her back to discovering her anger at the injustices of her childhood, and taught her how she had emotionally and mentally retreated from the world, learning a pattern of ‘getting away’ or provoking others to keep away from her.

Using the vocal mirror and the triangle of insight provided the touchstone for Mary to discover that the reactions she evoked in others through her voice projected onto the outside world her inner emotional reality that she had worked so hard to escape and ignore. Much of her life (she was in her early fifties) had remained ‘unspoken’ to the extent that when she first came to me, she felt completely incapable of talking about her inner life and childhood wounds, or changing her pattern of body use to support her voice. This process helped open the door once more to her inner life, so that she could begin to understand herself.

Applications of the Vocal Mirror

The strength of this technique is fourfold. First, it reveals to the client motives that were hidden sometimes even to herself, raising her level of awareness. Second, the client controls the content and degree of insight, so the method is ‘safe’. Third, the therapist does not have to ‘second-guess’ the client, formulate any hypothesis, or impose any interpretation. Fourth, since the client makes her own discovery about herself, she is much more prepared to accept her findings; so the degree of personal responsibility increases also as does the commitment to change.

The Vocal Mirror can be used to make sense of what is happening ‘right now’ in an apparent impasse. It can also be used to help a client consider what patterns she may have with others, and how these operate. It may also help a client reach back to understand more about a relationship or events from the past. Which of these is explored depends on the goals of the session, and the nature of the contract with the therapist.

On one hand, the Vocal Mirror is a diagnostic tool in which, supported and guided by the therapist, the client hears herself with new ‘ears’, and takes responsibility for the diagnosis of the ‘problem’. On the other, it is also a tool for change; for as the client’s awareness and responsibility increase, her relationship to her voice and the problems changes. Diagnosis and healing become a single process, and both are placed firmly in the hands of the client.

The risks of intervention

The therapists I have trained in this technique (and I) have found two common experiences when using the Vocal Mirror. First, as therapist, we can be anxious that we won’t do a good enough ‘performance’, that we will get it wrong, or do it too inaccurately. Second, we can be anxious that we will offend or upset our client by performing a Vocal Mirror.

It is common for the client to report that she is interested in being mirrored, although she is anxious about what will happen. When the Mirror starts, she is often horrified and shocked. However, there is a strange fascination about the exercise, and almost always the client opts to continue so she can struggle with it and try to make sense of it and learn something from it. Despite the therapist’s ‘performance anxiety’ about getting it wrong, even if the Mirror is apparently inaccurate, clients usually report that the experience is enormously valuable and informative.

I can’t remember who first said, “There should be two frightened people in the consulting room, the client, and the therapist.” Notice how in this exercise there can be trepidation on both sides, and both people have to take a risk. In so doing, much can be gained. The technique is experimental in spirit; the client can say it didn’t work, or that she didn’t recognize anything of herself or others in the Mirror or her reactions to it. The therapist can agree to let it go again without further comment. I have used this technique many times, and it has never failed to reveal important information and move things on. Only once did a client say that it didn’t ‘work’ for her, or ring true at all. But she then referred to it several weeks later and admitted that she had lied, and that the experience had been so raw and revealing that she had wanted to dismiss it at the time in order to ‘put me off the scent’. Had my timing therefore been ‘off’? Perhaps not. The lying and the later ‘owning up’ was part of the work that needed to happen, as was the client’s experience of my acceptance of her need to lie initially. She was also intrigued to discover I felt no need to forgive her as I did not feel wronged – her own self-punishment for lying was far greater than anything I could have meted out anyway!

References

- Jacobs, Michael (1988) Psychodynamic Counselling in Action, Sage, London

Alexander Massey has taught voice for over 30 years, and worked therapeutically with people for the last 20; he is an experienced professional singer, teacher, and workshop facilitator, offering workshops and consultations in both the UK and Sydney, Australia. He works with singers and actors, broadcasters, voiceover and recording artists; people recovering from addictions, abuse, and trauma; voice teachers and coaches, and therapeutic voice workers; counselling services and therapy training organisations; theatre companies and choirs; music therapists, speech and language therapists, psychologists and psychotherapists. His work has also taken him into helping people with voice and communication issues in the workplace, with organisations such as the London Underground, Oxfam, Unilever, St James’s Place, and Hampton Court Palace. He is a member of Equity, and at different times been member of the British Voice Association, Natural Voice Practitioners Network, and the Association of Teachers of Singing, and a published writer in several of their journals.